How Satya Revolutionised Hindi Cinema

In the year 1997, one of Hindi cinema’s all time greats ventured into the ‘urbane’ territory. His characters were finally refined, colloquial language spewing younglings, not poetry reciting old souls. The people who played them? Good looking, genial Hindi film folk, the kinds that had a penchant for saccharine-coated stories. Many speculate that the thespian sought advice from his in-demand son to adapt to the approaching millennia’s ‘cool’ factor. But his affection for ‘happy endings’ ensured soaring ticket sales.

Roughly ten months later, one of his movie’s many hit songs plays in a chawl-like apartment, as a young boy admonishes his mother for the oft-repeated bread-butter breakfast. Seizing a way out of eating it, he rushes to answer the knocking on the door, only to allow in a barrage of policemen who attack his father. The song, ‘Arre re arre re kya hua’ is brutally massacred by growing sounds of protest. And that moment alone goes on to define the whole of Satya, Ram Gopal Varma’s no holds barred take on Mumbai’s underworld.

In the relatively fruity year of 1998 came a grim tale that aimed to showcase the city’s dark underbelly, with characters prone to self-destruct. The city’s violence, until then, had only been captured from the eyes of do-good men who rebelled against injustice with their morality intact. Made iconic by Amitabh Bachchan specifically, cinema’s goodness was shouldered by characters who could do no wrong. And there was a principled justification behind that depiction. After all, India had always been obsessed with good triumphing over evil, to mythological proportions. The audience felt validated applauding the success of the good man, so good men they got.

In the relatively fruity year of 1998 came a grim tale that aimed to showcase the city’s dark underbelly, with characters prone to self-destruct. The city’s violence, until then, had only been captured from the eyes of do-good men who rebelled against injustice with their morality intact. Made iconic by Amitabh Bachchan specifically, cinema’s goodness was shouldered by characters who could do no wrong. And there was a principled justification behind that depiction. After all, India had always been obsessed with good triumphing over evil, to mythological proportions. The audience felt validated applauding the success of the good man, so good men they got.

In Varma’s Satya, there was no moral brigade. There were no big, ruthless men trampling over the weaker good. There does not a messiah rise, in agitation. And nowhere (spoilers ahead) is the happy ending everyone was so prone to watching. Satya was just a depiction of men, united by their love to rise to power, and divided to beat the other to it. Perfectly encapsulated in the one moment when the titular character is handed a gun for the very first time. Now, the averagely good Hindi film protagonist might fear that sudden rush of responsibility. He might be angered by it, too. Our Satya only bemuses, “But I don’t know how to use it.” He’s more confused by his ineptitude than the villainy of the machine. Gritty stuff, this.

But what made Satya go on to become the gangster-genre defining piece of cinema in India? We decode the many reasons that made, and continue to make, Satya work.

An unforgiving protagonist

Just two years earlier, Varma gave Indian cinema one of its most endearing characters. Rangeela’s Munna was a ruffian full of street smarts, but one blessed with a heart, real pure. A character who wouldn’t think twice before walking away from the woman he loves, so she can be with the man he thinks she’s in love with (who his he, himself, much to his amusement).

Just two years earlier, Varma gave Indian cinema one of its most endearing characters. Rangeela’s Munna was a ruffian full of street smarts, but one blessed with a heart, real pure. A character who wouldn’t think twice before walking away from the woman he loves, so she can be with the man he thinks she’s in love with (who his he, himself, much to his amusement).

Satya, on the other hand, evoked Howard Roark-level objectivism. A keenly individual character, his rise up the ranks is determined by his sheer ability to never compromise. Satya is no villain, but he’s no hero. As an immigrant wanting to make things work in Mumbai, he is only characterised by taking everything head-on. Interestingly, Satya brings to mind many iconic characters of Indian cinema, because of one common trait. A trait, that finds no justice in its English translation. Called ‘khuddaari’, Satya is out and out, ‘khuddaar’. One who doesn’t tolerate any misgivings against him. For what was the first time, Hindi cinema was treated to a morally ambiguous character, one who blushes when teased for his first murder, but who riles up when teased with the woman he desires. It made possible for movies to be centred around someone without a heart of pure gold, otherwise unimaginable!

Colourful, drawn-from-life characters

Varma, in several anecdotes over the years, has cited real life as inspiration for some of his strongest characters from Satya. Everyone from Kallu Mama, Bhau and Chander brought in a unique insight into the storyline. The one towering above them all, is the character everyone walks away with – Bhiku Mhatre. Made enduring with his one line, “Mumbai ka king kaun? Bhiku Mhatre!” that is sure to elicit applause if the movie were to run ever again, the character is both funny and menacing. Quick to slap his stubborn wife into submission, while playfully teasing her moments later, Manoj Bajpai’s portrayal of Bhiku Mhatre’s inherent child-like quality continues to keep the character likeable, inspite of the persistent moral ambiguity.

Varma, in several anecdotes over the years, has cited real life as inspiration for some of his strongest characters from Satya. Everyone from Kallu Mama, Bhau and Chander brought in a unique insight into the storyline. The one towering above them all, is the character everyone walks away with – Bhiku Mhatre. Made enduring with his one line, “Mumbai ka king kaun? Bhiku Mhatre!” that is sure to elicit applause if the movie were to run ever again, the character is both funny and menacing. Quick to slap his stubborn wife into submission, while playfully teasing her moments later, Manoj Bajpai’s portrayal of Bhiku Mhatre’s inherent child-like quality continues to keep the character likeable, inspite of the persistent moral ambiguity.

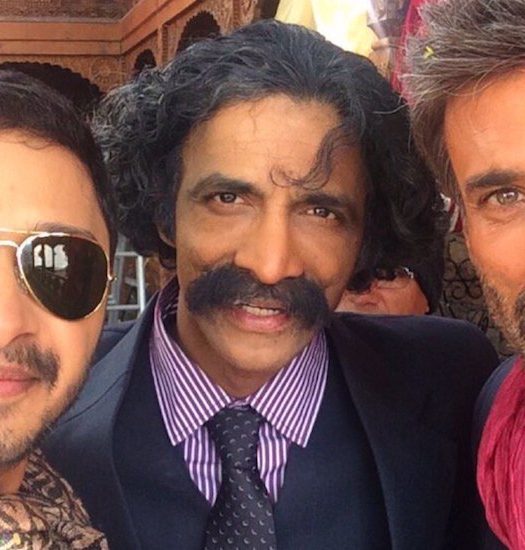

As Anurag Kashyap and Saurabh Shukla, who also essayed the role of the loveable goofball Kallu Mama, had it, the script was full of characters that had towering individual personalities. In the midst of them all, Satya would just drift along, thereby making him as much passive to their nature, as the audience was. Over time, you realise, you’re not just watching Satya’s journey, you’re watching Mumbai as it was, as Satya himself, making peace with the circumstances, because you only want to know more.

The process is made relatively easier by realistically portrayed actors, most of them unknown. After Rangeela’s chart-busting success with superstar Aamir Khan in the lead, it was of most wonder why Varma would cast southern face J D Chakravarty as the namesake protagonist. It works because not only is he new to the city, he’s new to the viewer as well. The lack of glamour and pretence only helps make the film as starkly real as imaginable, with Hindi cinema’s then most glamorous Urmila Matondkar reduced to pleated cotton sarees and poor-class demureness as well.

One aspect worth noting is Varma’s ability to etch out actual people from beneath the characters. Hindi cinema, up until then, treated its villains with apathy, by allowing the audience to gaze at their villain from a distance. In what was a first, Varma would take characters caught in the midst of the city’s crime route, give them families, give them songs, and alcohol sessions, and flesh out actual people. You do not come out feeling strong sympathy for the characters, but you know about them enough to care.

Mumbai, the protagonist

Mumbai, the protagonist

Just three years before Varma’s Satya came another visceral take on the city, Mani Ratnam’s emotional Bombay. While the movie tore at heartstrings with a climax that aimed at establishing agreeability, the kind only the city knew how, Varma’s Mumbai is a more rasping spectator to everything that could possibly go wrong. In his city, producers could get murdered in the middle of the city, and a man could cause a stampede in the movie theatre with the shot of one bullet. But the city that gives is the city that takes. In Satya, Mumbai stands a mute spectator to all the unflinching gore taking place. It established a new character for the city, often synonymous with being the place of dreams, where everything is alright.

While Mumbai is known to be a city of astounding paradoxes, the absence of the shiny and flashy helped keep the tone of the movie intact. A tone that would then inspire several more filmmakers, one of them Kashyap himself, whose movies went on to have the city as their gravelly backdrop.

Riveting background score

With Shiva, Varma established a keen understanding of the contribution a good background score could do to a movie. With Satya, he took that to another level by involving his keen loyalist, Sandeep Chowta to come up with an entire track list of background scores, complete with thematic anthems awarded to each of the significant characters.

One of the biggest highlights of the background score that could do well explaining its sophistication is the symphonic orchestration used during action scenes, than the usual hammered sound effects popularised by Hindi cinema. The haunting sound effects only helped add several more layers to the characters.

Realistic cinematography

This wasn’t a movie shot wherein the beauty of the city was amply explored. Even a shot at Marine Drive is bound to retain the monochromatic elements that dominate most of the movie. Instead of exploring the city’s largeness, the movie attempts to go into its bylands where crime dwellers lie. Most of the scenes will take you into box-like rooms and houses and narrow streets, letting you understand the movie in a far more intimate manner.

Satya is characterised by the many quick cuts throughout the film. It’s most common to find a scene cut just when the knife has hashed a face, or a bullet has entered the body. This wasn’t something commonly practiced in Hindi film editing, even the action scenes. But the quick cuts helped keep the viewer attentive at all times.

Satya’s looming influence

Satya’s looming influence

Satya boasts of many things – introducing Anurag Kashyap in a grand manner to Indian cinema, one of the more beautiful Vishal Bhardwaj – Gulzar soundtracks, riveting real-life characterization, Manoj Bajpai as a fearless actor worth great scripts, and enabling performers for characters. The movie is admired to this day for its great attention to detail, and for its ability to retain the realistic element through and through.

READ: OUR CRAFT CAN’T BE EXPLAINED

In the midst of over-the-top melodrama infused work, Satya came across as a game changer, so much so, that there continues to be a ‘Satya’ in every realistic film you see made in India today.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed within this POV/BLOG are the personal opinions of the author. PANDOLIN is not responsible for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information on this blog. All information is provided on an as-is basis. The information, facts or opinions appearing on the POV/BLOG do not reflect the views of PANDOLIN and PANDOLIN does not assume any responsibility or liability for the same.