No permissions were taken, I was completely on my own – Chandrasekhar

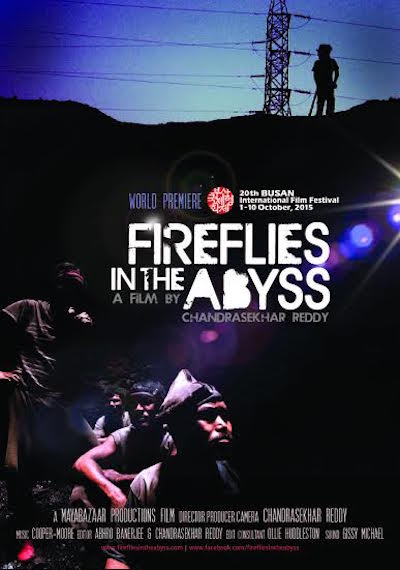

Chandrasekhar Reddy’s first debut feature length documentary Fireflies in the Abyss has been receiving accolades all over the film festival circuit. And very rightly so. The film goes deep into the coal mines of Meghalaya to reveal the hard lives of the miners and the brutal choices they are forced to make at every turn of their lives. Reddy’s central character is a kid named Suraj who was born in the mines and knows no other life.

In a freewheeling chat with Pandolin, Reddy talks about how he discovered his subject, the challenges faced while making the film and why Drishyam Films is the perfect platform to take the film forward.

Chandrasekhar Reddy

When did you first learn about the issue of coal mining and decide to document it?

It was back in 2011, when I had gone to Meghalaya to research for another film. That’s when I discovered all that was happening there. I had no clue about the things I documented. Children working in the mines is also something that I got to know much later. That was a great entry into discovering how people migrate from Nepal and Bangladesh to work in the mines. Also how people are fighting for coal mining lands. There were many issues to explore. Gradually I began researching. Initially I was there only for a week. But by then, I had understood that the documentary would revolve around a kid. So I befriended a group of kids and made a short three-minute trailer to raise funds. Subsequently I came back, read up on the subject and made several other visits. The research and waiting for funds took about nine months. Once I reached Meghayala, after the pre-production work, I was there for close to six months and what you see in the film is pretty much what happened there during that time.

READ: FIREFLIES IN THE ABYSS SELECTED AT THE PRESTIGIOUS 2016 HOT DOCS

How difficult was is it to get permissions to shoot in the mines in Meghalaya?

I had to find a right time and right situation to shoot. It wasn’t a report that I was doing on mining and it’s workers. Had it been a news report, I would have gone there, shot for 2-3 days and be back before anybody realised what I was doing. But I wanted to shoot the characters for several months, so first I had to find the right people, then ensure that it was a safe situation to shoot in and at the end of the day, something needed to happen in and around the characters for the story to progress. I didn’t want to do a collection of interviews and shoot some mining shots and put it together. In the six months that I was shooting the characters who are there in the film, I didn’t know for how long I could continue shooting them because anytime, anybody could have come and stopped me or refused to let me document them. But gradually the matter progressed organically to become a film.

There weren’t any permissions taken. I was completely on my own. Some people thought I am doing some geological research while I told some that I am shooting a tourism video for Meghalaya. So I had to invent stories suiting the time and person I was talking to.

How did you fund the research & shooting? Did you have a producer from day one?

Initially I began the shoot without funds. I had a camera and shot everything myself. In the 9 months that I was waiting for the funds, slowly it was getting difficult to go to the place that I wanted to shoot in. There were stories of people who had gone there and were attacked. That’s when I thought that the more I wait, the more difficult it will get. I had to start shooting immediately. I took the camera and traveled to the place.

In the meantime I had applied for the funds and during the course of my being there, the funding came through. Initially I didn’t have money to hire a crew but later I discovered that even if I had funds, I still wouldn’t be able to exist there with crew members. It would be impossible. So I ended up shooting the documentary myself, doing the camera, sound, interactions, direction, everything. It was a one-man shoot.

Fireflies in the Abyss Poster

How have you captured the claustrophobic alleys? Also wasn’t lighting a challenge while shooting in mines?

There were several challenges. One of course was the technical challenge like of not having lights in the mines. So I used torches, put a bunch of them together and used that. I used a GoPro, which is a very small camera. That was the only camera I could take inside the mine. It was a very wet and dirty space. Even if I had taken a small DSLR camera it would’ve still been difficult for me to shoot. So I shot all the mining sequences with a GoPro. Also it was a completely hand held shoot. The moment you place a tripod, people even from a distance can recognize that you are doing something there, something professional. But when you have a camera in hand they don’t mind much. You appear more like a tourist. So these were some of the technical challenges.

The bigger challenge was finding a safe situation and the right people, and that took a lot of time. Once you find such people you have to gain their trust for them to open up to you. You need to build an intimate rapport with them for them to talk to you unabashedly, reveal their true selves to you. That to me was a bigger challenge. And yes the challenge of keeping away from the people who don’t want you to be there. Now when I think about it or talk about it to people, I question myself, “What was I even thinking!” Anything could have happened. But once you are in the situation, completely invested and you’ve spent a long time to find the right situation, you don’t want to let it go.

READ: FIREFLIES IN THE ABYSS WINS TOP AWARD AT IDSFFK

Were people comfortable and open to the idea of speaking in front of a camera? How did you build a rapport with them?

To make a rapport with them I just had to be a part of them, live like them, live with them in their shacks. The advantage was that everybody who comes to the mine is a stranger. Nobody really knows each other. Everyone is an immigrant labour. People open to each other must faster, you might not build close ties but the relationship grows faster. Although they were curious about why I was there with a camera, once I started staying with them, doing exactly what they did like getting up at 4 am in the morning, going to the mines, in the evening they used to smoke beedis and drink local liquor, so I would sit with them, share stories and they became comfortable. So in one way I was a miner, except that they had mining tools and I had a camera. That’s how I gained their trust.

You do everything they do and become part of them. Soon they ignored the camera and thought I was just roaming around without purpose. As for the main character, Suraj was an 11-year-old bright boy, spunky, chirpy and very curious about things. He had his own life so he didn’t have that much time to question my intentions. He just enjoyed me being there. I established a friendship with him and he began trusting me. That’s how things grew.

It is said that you had to make multiple visits to the area. How long did it take you to shoot and at what point did you decide that you needed to move to the edit?

It was completely decided by what happened there. When I first began following Suraj, he was living with his family. His family was only his dad as his mother had passed away and his support system was his elder sister. Two weeks into discovering him, his family decided to shift back to Nepal. He told me that he isn’t going back, he was born in these mines. “This is what I know and Nepal is a strange place to me, I don’t want to go there”.

The family tried convincing him but he didn’t agree so they left without him. After some days, Suraj too disappeared. I had to go and search for him. Finally when I found him, he was living with older boys, 18-19 year old boys, who were also into mining. They had put some money together to support him. He joined a school nearby. And that’s when I thought that I’d found the perfect end. A year later I returned to the place, to see how Suraj had progressed, and shot some more with him.

Still from Fireflies in the Abyss

How did your association with Drishyam Films happen? How has that given an impetus to the film?

I knew of Drishyam Films because of the fantastic films that they’ve been producing. Also when I heard that Shiladitya Bora who was associated with PVR Director’s Rare has joined Drishyam and that they are also getting into distribution, I thought that he’d be the best person to talk to about distributing this film. Meantime the film had also been doing rounds of various prestigious film festivals receiving a great response in Korea, Toronto etc. No one knew me or my work at these festivals and had no idea of what is happening in this part of the world or this issue, yet they accepted the film so warmly. They responded to it and that gave me confidence to take it to the vast audience and release it in theaters.

In India, documentaries are shown in certain spaces or do 2-3 rounds of festivals and that’s it. The end of its life. But after what I had put in, the four years of hard work to make this film, I could definitely put more work to get it released. I thought I should share it with a wider audience. I think meeting Shiladitya and the people at Drishyam was a right thing to do because they can put their expertise in distributing and releasing the film. They know the dynamics of the job, how many theaters the film should open with, how to progress with the film, etc. The things I don’t know and wouldn’t understand even if I spent another four years in it. They are the best people to handle it and take the film forward. Also I think that they were looking for documentaries worth taking to theaters. It works for them, for me, the documentary and documentary makers around the country and independent films in India at large.

READ: DRISHYAM FILMS TO RELEASE DOCU FEATURE FIREFLIES IN THE ABYSS

What next are you working on? Do you plan to work in the fiction space as well?

Yes I am looking forward to working in either the documentary or fiction space. I am in the process of meeting people and researching a project. It takes a while to get the material together, raise the funds. Also for me there isn’t much of a difference left in fiction and non – fiction these days. The distinction is blurring, with so many mediums cropping up. Internationally also lot of fiction is being made like documentaries and vice versa. Interesting work is happening everywhere and people are talking about new media. Things are changing in the way you are showing films using Internet, multimedia et al, which are all legitimate ways of presenting creative work. And I think things are actually unfolding in superior ways and that’s what I am more interested in. So many possibilities are available, so I look forward to getting on to my next film.

Fireflies in the Abyss will have a Pan-India release across major metro cities on July 1.